How to edit your movie to create empathy

Editing – it’s a skill. It can inform your film with so much and it can also help you to uncover so many subtle layers within your movie. Good editing can transform your film into something you never imagined and like Joe Dante once said: “Many a great film has been made and lost in the editing room.” So before you go into it with a large pot of coffee and start watching the hours and hours of raw footage, just keep that in mind. Today we’re turning our focus to how to create empathy with the editing process by looking at some of the techniques used by the great filmmakers of modern cinema. Let’s get stuck in, shall we?

What to show and what not to show

In the past (not the 90s, but the real past) there were a lot of things that you couldn’t show in a film. But sometimes you didn’t have to show the controversial moments for audiences to know what was going on. Does the audience need to see the kids who’ve been given the tampered penicillin in The Third Man? Do we need to see what’s in the bucket in Alfie? No, we don’t.

You can film them if you want, but when you get to the editing room, think about whether the audience really needs to see that footage. Each audience member will have an imagination of their own and that will surely be enough. This is a technique used to perfect effect by Jacques Tournier in Cat People, which is considered the first horror film in which you don’t see the true horror until the very end.

Overlaying sound

Whether it be The Godfather, The Conversation, or Apocalypse Now, Francis Ford Coppola knows how to edit his films with incredible style. In The Godfather, for example, as Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) sits in the restaurant talking to the men who tried to kill his father with a gun in his pocket, we don’t just hear the sound of the restaurant or the men talking; we hear a train in the background. The train builds the tension and perfectly reflects Michael’s mindframe before he stands up, the sound of the train stops, and gunshots are heard instead.

A million ways to tell a story

Five shots from five different angles will tell a story in many different ways. Try to tell them all before you make your final decision, as each one might bring up something new that you hadn’t thought about before. Director Akira Kurosawa’s drama-mystery Rashomon doesn’t really do this in a technical sense, but more of a storytelling way, so it’s more the ethos of the movie that you need to remember. The line that in life “there is your version of the truth, our version of the truth, and the truth itself” is never more evident than in Kurosawa’s masterful lamentation on the notion of truth.

The audience’s POV

A few years ago, Werner Herzog proved that he genuinely couldn’t care less about other people’s opinions and decided to remake (or at least, re-something) the harrowing classic, Bad Lieutenant. The film borders on the unwatchable at times, but it’s worth remembering for the scene in which Herzog totally flips the film and shows the audience the POV of a lizard who just happens to be there. Although a lizard’s POV might be an extreme example, if you’re looking to create empathy with certain characters, it’s good to switch it up and show your audience the film from various angles and perspectives.

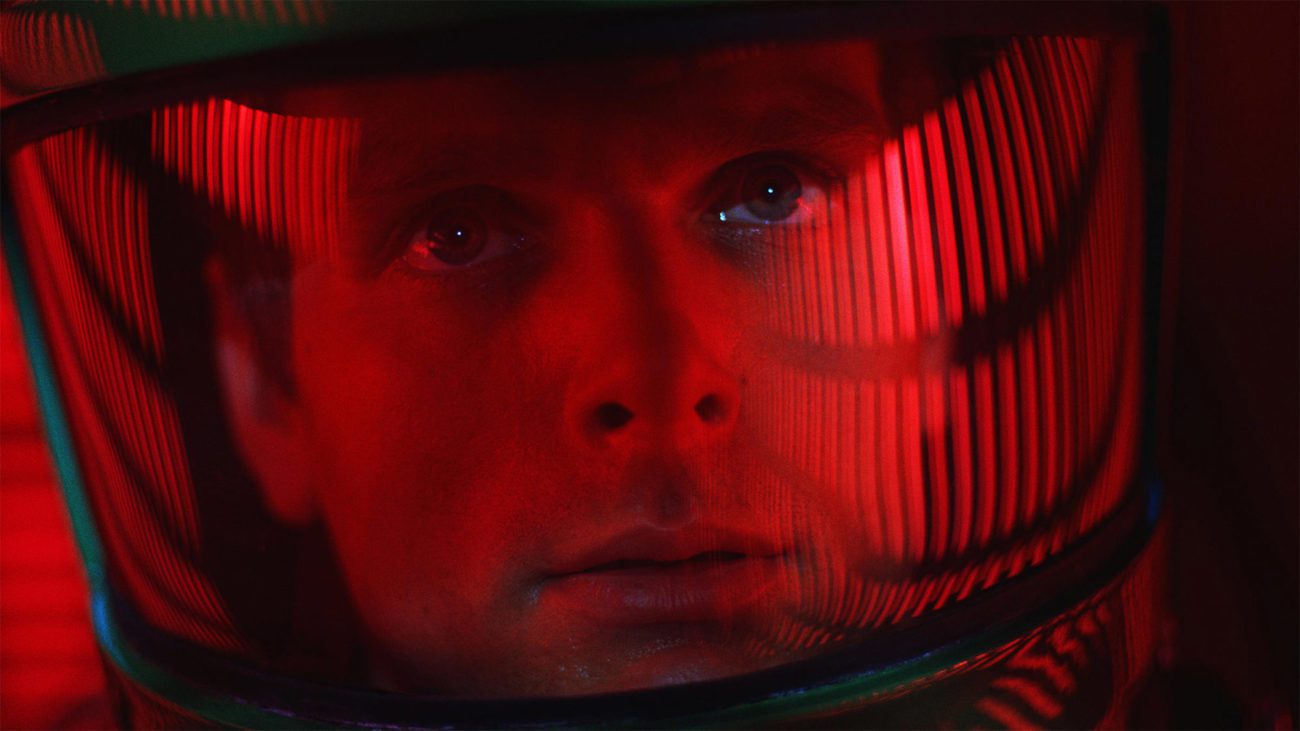

Match Cuts

Hands down, the most famous match cut in film history is from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. As a caveman throws a stick into the air, it quickly becomes a space station, floating through space. In one match cut, Kubrick pretty much sums up a million years of human evolution. It’s an iconic image and one that young filmmakers and editors can learn a lot from. So when you’re editing your film and you’re changing scenes, always remember that creativity doesn’t end there. Think about match cuts that you might be able to use, and if you can’t think of any, just parody 2001. People have been doing it ever since it came out, so at this point it just belongs to the ages. And who knows – you might do it better than Kubrick did? (You won’t, but you can always try.)