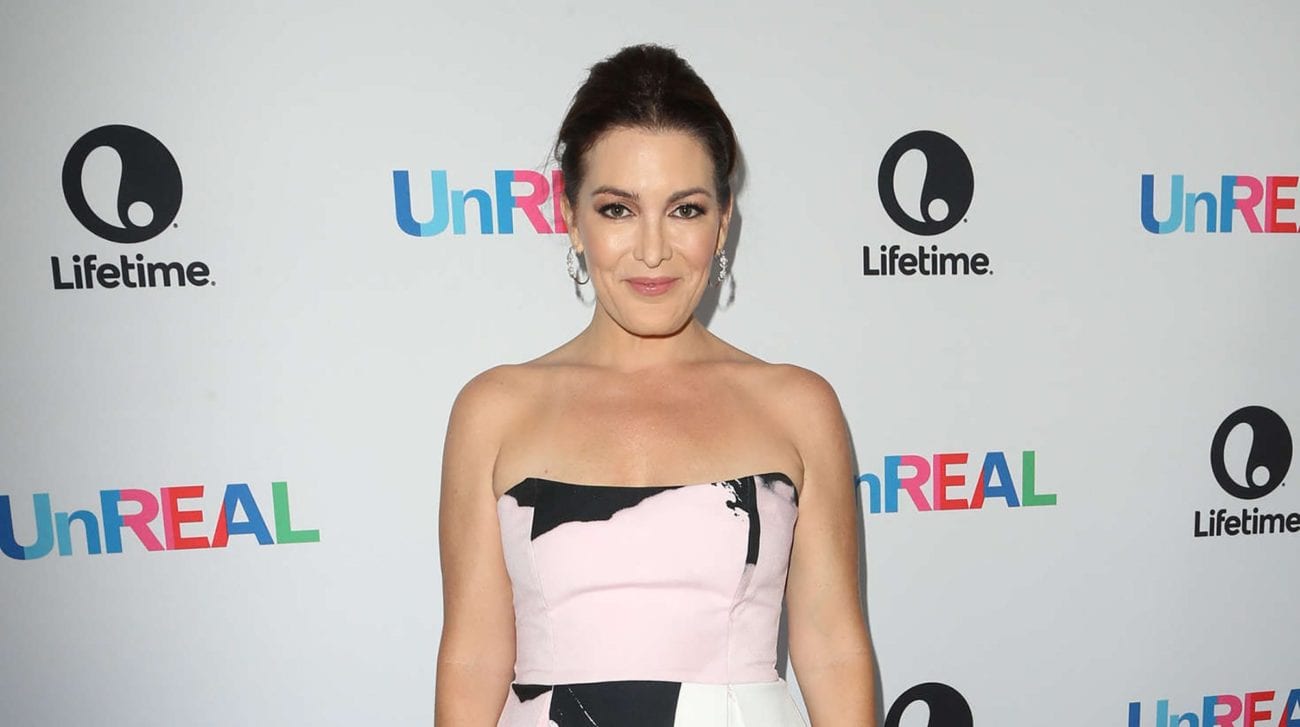

Is life ‘UnReal’ for TV showrunner Stacy Rukeyser?

Since season one of the show, Lifetime’s UnReal has garnered a name for itself as one of the most compelling female-led TV dramas currently airing. Following the production of a Bachelor-style reality show called Everlasting – and the often unscrupulous manipulation taking place behind the scenes to make the show a hit – UnReal offers dark insight into an industry currently under fire.

With season three of the show premiering February 26, we caught up with showrunner Stacy Rukeyser to talk about the show’s pertinent themes, the need for complex female characters, and how movements like Time’s Up and #MeToo are impacting the industry, and the future of UnReal and Everlasting.

Film Daily: Since season one, UnReal has addressed issues that have become prominent topics within the industry. Why do you think so many of these issues (like gender disparity, sexism, and workplace abuses) are only being taken seriously now?

Stacy Rukeyser: That’s a good question. I think in our current situation there is a group of very, very brave women who finally have have had enough. It’s that great line from Network: “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore.” Maybe it was Trump becoming president, maybe it was the way we’ve all felt disregarded and discounted and oppressed, but they finally had enough and came to the fore. Finally we were talking about it in a way that seemed shocking enough to get people’s attention – and you have people in the industry finally paying attention.

It’s no secret that Hollywood has been a boy’s club for a long, long time. So women have been fighting to get a seat at the table and be taken seriously for a while. Some of us have been getting through, but certainly not a majority. I feel very indebted to the women who really were so brave. But for us on UnReal, the third season was written before there was even a “hashtag #MeToo” moment. We had this completely in the can and it was edited last August.

We started pitching the idea of Serena, the feminist suitress of season three, back before Trump was even elected. At the time everyone in Hollywood thought Hillary Clinton was going to become the president, that we were on the cusp of a bright new future for women. So all I can say is the writers and I – women and men – we’ve experienced things in Hollywood as well as in the wider world and we’re very excited to have a chance to write about them. The fact that UnReal has anticipated this cultural conversation feels very fortuitous.

Serena, the lead suitor of season three, is a powerful 30-something venture capitalist whom the average guy seems to find terrifying. What drew the UnReal team towards this specific character?

The storyline was very personal to me as well as to Sarah Shapiro, the co-creator of UnReal. I was 37 when I met my husband and I had really gotten to the place where I thought it wasn’t going to happen for me: I probably wasn’t going to get married and I probably wasn’t going to have kids. And it was sort of okay for me, because my career was going well – but it was certainly sad for me, frustrating and confusing. I didn’t understand why I was having these difficulties that I think a lot of women have, which is that as you climb up the ladder at work, often it becomes harder and harder to find a man.

When you say a smart, strong woman can be terrifying to men, I think that’s really right, and it’s maddening and unfair. As women we’re taught at work we should be aggressive: “You go, girl!” and “You lean in!” and “Get a seat at the table!”, “Demand equal pay!” and “reclaim your time!” and all the rest. But when we’re on a date, we’re expected to magically transform into this other creature who is much more demure in a much more traditional definition of femininity – perhaps with fewer opinions! So that’s really confusing; thank god there are some men out there who aren’t frightened by strong women.

In terms of Hillary Clinton and that “bright new future”, it was also a little bit scary to me because on the campaign trail I really saw that, to a great portion of this country, there is nothing scarier than a smart, strong woman. And so in the first episode of season three, that’s where that line comes from: “You’re smart, strong, successful – half of America already hates you.” Unfortunately, I think that’s true and so, so sad. All I know to do about it really is to write more characters who are smart, strong women and to show their vulnerabilities and their flaws and their complications as well as their strengths – hopefully to allow viewers into their hearts and minds for a greater understanding of women and people. And then maybe we can start to change the hearts and minds of America and beyond. I don’t know, we’ll see.

The writing on UnReal takes the plot to some dark, but unnervingly real, places, but it also manages to maintain the humor. How do you and the team strike that balance?

We always start with the Rachel & Quinn story. As an example, by the end of season two we had a lot of big plot points we didn’t have the full chance to explore from an emotional or psychological standpoint.

Rachel had revealed she was raped by one of her mother’s patients when she was 12 years old. She had also been committed to a mental institution and had some part in Jeremy killing two people, and that’s a lot, right? So when we started season three, I didn’t want to ignore that any of those things happened, but I wanted us to sit in Rachel’s heart and soul and see where she would go from there. That’s when we had the idea she would have removed herself from her life, that she’s trying to live an honest life. Of course, the one thing she’s not being honest with herself about is the part she had in Jeremy killing Coleman & Yael.

Rachel’s in complete denial at the very beginning, saying how she was just venting to Jeremy and she had no idea he was going to do something, while he’s saying, “That’s not true – you told me to do it.” Rachel really has to take a hard look at herself. She talks to a real shrink for the first time and he not only helps her to take a look at that but unpack where that darkness inside her comes from. We knew we wanted to go down that road and then it very quickly becomes a family story, because it’s about what her parents knew or didn’t know, and how they allowed her to process what had happened.

For Quinn, at the end of last season when she found out she can’t have kids, she preemptively broke up with her boyfriend, and that was fine because her career was going really, really well and that’s how she self-identifies. But as we start this third season, the show has been shut down for six months and her reputation in the industry has taken a real hit – it’s much harder for women to come back from a scandal than it is for men – and you see the personal desperation within her. How important it is to her she gets her empire back on track. Rachel can see how personally important that is to Quinn and therefore wants to make that happen for her.

Of course, that’s complicated for Quinn by Chett having his new 24-year-old swimsuit-model girlfriend and saying this new relationship is “easier.” That’s so maddening – this implication that who Quinn is was somehow responsible for her relationship with Chett not working out. By the end of the season Quinn has to decide: is that empire enough, or does she need a human connection beyond her relationship with Rachel?

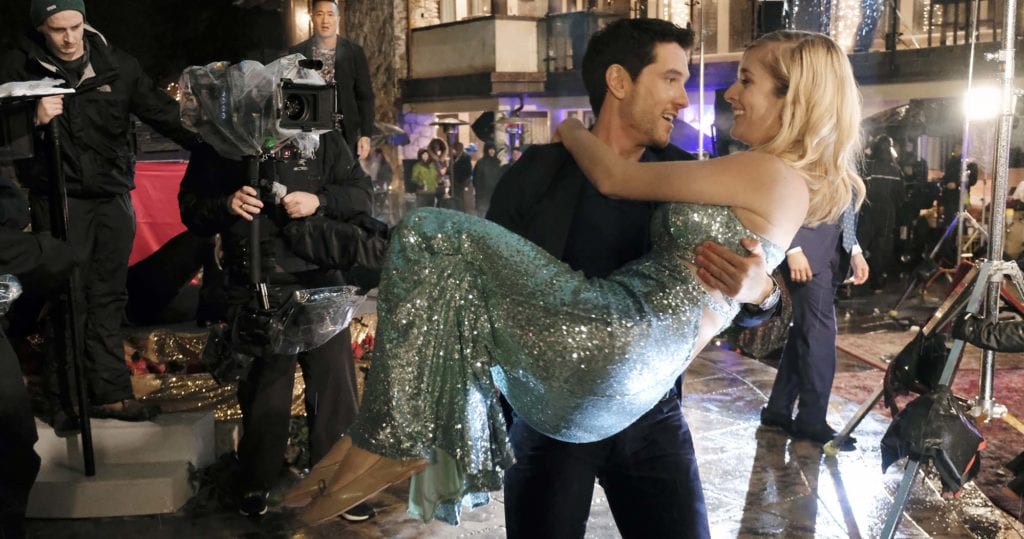

So that’s where we start. None of that is the zingy oneliners or the fun or any of that. But we started with that, and then with Serena and knowing we wanted to do the feminist suitress. But then you get to the “fun part”: who are the guys? And what’s happening on Everlasting? That’s always the contrast with UnReal. There’s the beautiful butterfly people, as we call them in their beautiful sparkly clothes, and then you have the mole people living in the walls behind the scenes. It’s the same thing with the story.

You have the fun Everlasting story and the manipulation of the characters who are the contestants, and then as we’re going along and breaking out the scenes, that’s when the fun zingers and oneliners come out. But all of it is through a lens that tries not to be sentimental. Even when we’re looking at the deeper, emotional stories of Quinn & Rachel. Quinn isn’t a character who is sentimental; she’s incredibly tactical and will brush anything off – she doesn’t want to get emotional. And that lends itself to a tone which hopefully saves us from being treacle-esque melodrama.

You wrote an amazing op-ed for The Hollywood Reporter at the end of last year regarding the misogynistic atmosphere you experienced as a writer on One Tree Hill. Has that experience changed how you work now?

It really has. I made decisions, even at that time, about what I wanted to do if I ever got the chance to run my own show and who I wanted to be as a showrunner. I’ve had some great examples of showrunners along the way who’ve been incredible mentors to me and cared very much about creating a great working environment for people on a show.

Because television is such a collaborative medium – the writers, the actors, the directors, the crew, the post-production, the editing – there are so many people who go into creating UnReal. I want all of them to feel ownership of the show and that they were a part of creating something great – and that the process of creating it was itself great too.

So I make sure that my writers room, to begin with, is a safe space. You can imagine we talk about pretty bawdy, outrageous things, often in a tough way, but it’s a safe space to have those conversations. It’s clear those bawdy, outrageous things are never to be directed at someone. You can talk about the characters and the story, but you have to have an awareness of your writers and make sure that people feel comfortable.

I also make sure my writers know that, if they don’t feel comfortable, they can come to me. In the week when all the people were in the press who came out against Mark Schwahn and Andrew Kreisberg – a very prominent showrunner – I went up to Vancouver for a table read of one of our episodes and made an announcement there about how much I really cared about this, and how important it was to me that everyone feel safe. I wanted to make sure they all had my phone number and they knew that they could call me day or night, that something would be done about it, and that I take these things very seriously.

To me it just didn’t feel like that big of a deal, but I think to the people who experienced it, it was a very big deal because not every showrunner is doing that, taking these things as seriously. I feel that working in television is the most fun job in the world, and that having an awareness about making sure other people feel safe and comfortable at work does not take away any of the fun factor at all. That’s always an excuse – like, “Oh, we need to be free to talk in the writers room”, or “Oh, it’s Hollywood! Can’t we be a little looser?” – all those things are true, but no one has to feel uncomfortable or unsafe to make that happen.

As a show within a show with plenty to say about women in the industry, how will movements like Time’s Up and #MeToo impact UnReal moving forward?

Season three was already done, and we reviewed it based on this moment in time. We didn’t change anything except for this one Charlie Rose joke which had nothing to do with harassment or assault or any of that, but it did need to be adjusted somewhat to address the current state of his reputation. But everything else really still works, and it does feel precious that we could feel these things and that this real change came. I don’t think we felt the change was coming – but there has been a change.

We have just finished shooting season four. The one thing I can say about it is it’s Everlasting: All Stars, so it has a different format. I don’t watch The Bachelor – I don’t actually watch any reality TV – but there are a couple of things about The Bachelor noisy enough that I’ve heard about them.

One was that they had the first African-American Bachelorette after we had an American-American suitor, so that was great. I also heard about the scandal or whatever you want to call it on Bachelor in Paradise where a producer made a complaint to the studio, and then they shut down production. It was a complaint about sexual activity going on that he or she was uncomfortable with – that the people involved were too drunk.

I found it shocking that this producer made a complaint, because that show has been on the air for about 20 seasons and no one had ever made a complaint. So I thought, “Wow, this has to have been really egregious for a person to make a complaint.” Sometimes, when you’re working on a crew, you don’t even know whom you could call at the studio. Now in the wake of #MeToo and Time’s Up, people are putting the number for human resources on the call sheet, but that never used to be the case. So it was a really big deal.

I was very intrigued by that whole story and it’s so much a part of what we talk about on UnReal: how much do they intervene? How much should they intervene? How much care do they take for the contestants – or lack of care, as the case may be? That was a bit of an inspiration for part of season four. Other than that, you just try to write from a truthful place for these characters, and certainly it’s influenced by the personal experiences that we’ve had. But it’s not as if we say, “Well, how are we going to do a Time’s Up story within UnReal?”, because we’ve been doing a Time’s Up story for UnReal since season one.

As a female creator within the industry, what do you personally hope to see come out of the Time’s Up and #MeToo movements?

What I would like to see, beyond a safe workplace for everyone, are more opportunities for female creators & showrunners: more stories with female protagonists, stories which feel personal to women, and female protagonists who feel real and complicated and flawed. That’s the kind of woman I am; the only kind of woman I know is a complicated, flawed character. I don’t think we’ve seen many of them on television yet.

I’ve certainly struggled a lot and pitched shows that I’ve been told are “too female”. But you never hear about a network saying, “Oh, it’s too male.” You always get the note, “Can you make your female characters more likeable?”, and that’s maddening. I think the solution to that is to make them more vulnerable and help the audience understand why they’re doing what they’re doing. If you look at Walter White in Breaking Bad, in the pilot episode you understand he’s got cancer and is trying to take care of his family – that’s why he’s doing this. I’ll give you that for a female character too! Let me tell a story where women aren’t always making good decisions.

That’s what I hope for: a broadening of the voices that are being heard in Hollywood. Along the way, if we can talk about creating a safe work environment, and the gender pay gap, and reasonable maternity leave policies, and all of the other issues that stand as impediments to women rising up the ranks in Hollywood and in all industries, then great. But I want it to go beyond that, towards increasing the number of shows and stories we get to see.